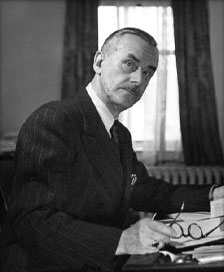

Paul Thomas Mann (UK: /ˈmæn/ MAN, US: /ˈmɑːn/ MAHN; German pronunciation: [ˈtoːmas ˈman]; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas are noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual. His analysis and critique of the European and German soul used modernized versions of German and Biblical stories, as well as the ideas of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Arthur Schopenhauer.

Mann was a member of the Hanseatic Mann family and portrayed his family and class in his first novel, Buddenbrooks. His older brother was the radical writer Heinrich Mann and three of Mann’s six children – Erika Mann, Klaus Mann and Golo Mann – also became significant German writers. When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Mann fled to Switzerland. When World War II broke out in 1939, he moved to the United States, then returned to Switzerland in 1952. Mann is one of the best-known exponents of the so-called Exilliteratur, German literature written in exile by those who opposed the Hitler regime.

Life

Paul Thomas Mann was born to a bourgeois family in Lübeck, the second son of Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (a senator and a grain merchant) and his wife Júlia da Silva Bruhns, a Brazilian woman of German, Portuguese and Native Brazilian ancestry, who emigrated to Germany with her family when she was seven years old. His mother was Roman Catholic but Mann was baptised into his father’s Lutheran religion. Mann’s father died in 1891, and after that his trading firm was liquidated. The family subsequently moved to Munich. Mann first studied science at a Lübeck Gymnasium (secondary school), then attended the Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich as well as the Technical University of Munich, where, in preparation for a journalism career, he studied history, economics, art history and literature.

Mann lived in Munich from 1891 until 1933, with the exception of a year spent in Palestrina, Italy, with his elder brother, the novelist Heinrich. Thomas worked at the South German Fire Insurance Company in 1894–95. His career as a writer began when he wrote for the magazine Simplicissimus. Mann’s first short story, “Little Mr Friedemann” (Der Kleine Herr Friedemann), was published in 1898.

In 1905, Mann married Katia Pringsheim, who came from a wealthy, secular Jewish industrialist family. She later joined the Lutheran church. The couple had six children.

Pre-war and Second World War period

In 1912, he and his wife moved to a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, which was to inspire his 1924 novel The Magic Mountain. He was also appalled by the risk of international confrontation between Germany and France, following the Agadir Crisis in Morocco, and later by the outbreak of the First World War.

In 1929, Mann had a cottage built in the fishing village of Nidden, Memel Territory (now Nida, Lithuania) on the Curonian Spit, where there was a German art colony and where he spent the summers of 1930–1932 working on Joseph and His Brothers. Today, the cottage is a cultural center dedicated to him, with a small memorial exhibition.

In 1933, while travelling in the South of France and living in Sanary-sur-Mer, Mann heard from his eldest children, Klaus and Erika in Munich, that it would not be safe for him to return to Germany. The family (except these two children) emigrated to Küsnacht, near Zürich, Switzerland, but received Czechoslovak citizenship and a passport in 1936. In 1939, following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, Mann emigrated to the United States. He moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he lived on 65 Stockton Street and began to teach at Princeton University. In 1941 he was designated consultant in German Literature, later Fellow in Germanic Literature, at the Library of Congress. In 1942, the Mann family moved to 1550 San Remo Drive in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The Manns were prominent members of the German expatriate community of Los Angeles and would frequently meet other emigres at the house of Salka and Bertold Viertel in Santa Monica, and at the Villa Aurora, the home of fellow German exile Lion Feuchtwanger. On 23 June 1944, Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. The Manns lived in Los Angeles until 1952.

Anti-Nazi broadcasts

The outbreak of World War II, on 1 September 1939, prompted Mann to offer anti-Nazi speeches (in German) to the German people via the BBC. In October 1940, he began monthly broadcasts, recorded in the U.S. and flown to London, where the BBC German Service broadcast them to Germany on the longwave band. In these eight-minute addresses, Mann condemned Hitler and his “paladins” as crude philistines completely out of touch with European culture. In one noted speech, he said: “The war is horrible, but it has the advantage of keeping Hitler from making speeches about culture.”

Mann was one of the few publicly active opponents of Nazism among German expatriates in the U.S. In a BBC broadcast of 30 December 1945, Mann expressed understanding as to why those peoples that had suffered from the Nazi regime would embrace the idea of German collective guilt. But he also thought that many enemies might now have second thoughts about “revenge”. And he expressed regret that such judgement cannot be based on the individual:

Those, whose world became grey a long time ago when they realized what mountains of hate towered over Germany; those, who a long time ago imagined during sleepless nights how terrible would be the revenge on Germany for the inhuman deeds of the Nazis, cannot help but view with wretchedness all that is being done to Germans by the Russians, Poles, or Czechs as nothing other than a mechanical and inevitable reaction to the crimes that the people have committed as a nation, in which unfortunately individual justice, or the guilt or innocence of the individual, can play no part.

Last years

With the start of the Cold War, he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism. As a “suspected communist”, he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he was termed “one of the world’s foremost apologists for Stalin and company”. He was listed by HUAC as being “affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts”. Being in his own words a non-communist, rather than an anti-communist, Mann openly opposed the allegations: “As an American citizen of German birth, I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged ‘state of emergency’. … That is how it started in Germany.” As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the Hollywood Ten and the firing of schoolteachers suspected of being Communists, he found “the media had been closed to him”. Finally, he was forced to quit his position as Consultant in Germanic Literature at the Library of Congress, and in 1952, he returned to Europe, to live in Kilchberg, near Zürich, Switzerland. He never again lived in Germany, though he regularly traveled there. His most important German visit was in 1949, at the 200th birthday of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, attending celebrations in Frankfurt am Main and Weimar, as a statement that German culture extended beyond the new political borders.

Along with Albert Einstein, Mann was one of the sponsors of the Peoples’ World Convention (PWC), also known as Peoples’ World Constituent Assembly (PWCA), which took place in 1950-51 at Palais Electoral, Geneva, Switzerland.

Death

Following his 80th birthday, Mann went on vacation to Noordwijk in the Netherlands. On 18 July 1955, he began to experience pain and unilateral swelling in his left leg. The condition of thrombophlebitis was diagnosed by Dr. Mulders from Leiden and confirmed by Dr. Wilhelm Löffler. Mann was transported to a Zürich hospital, but soon developed a state of shock. On 12 August 1955, he died. Postmortem, his condition was found to have been misdiagnosed. The pathologic diagnosis, made by Christoph Hedinger, showed he had actually suffered a perforated iliac artery aneurysm resulting in a retroperitoneal hematoma, compression and thrombosis of the iliac vein. (At that time, lifesaving vascular surgery had not been developed.) On 16 August 1955, Thomas Mann was buried in the Kilchberg village cemetery.

Legacy

Mann’s work influenced many later authors, such as Yukio Mishima. Joseph Campbell also stated in an interview with Bill Moyers that Mann was one of his mentors. Many institutions are named in his honour, for instance the Thomas Mann Gymnasium of Budapest.

Career

Blanche Knopf of Alfred A. Knopf publishing house was introduced to Mann by H.L. Mencken while on a book-buying trip to Europe. Knopf became Mann’s American publisher, and Blanche hired scholar Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter to translate Mann’s books in 1924. Lowe-Porter subsequently translated Mann’s complete works. Blanche Knopf continued to look after Mann. After Buddenbrooks proved successful in its first year, the Knopfs sent him an unexpected bonus. Later in the 1930s, Blanche helped arrange for Mann and his family to emigrate to America.

Nobel Prize in Literature

Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, after he had been nominated by Anders Österling, member of the Swedish Academy, principally in recognition of his popular achievements with Buddenbrooks (1901), The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924), and his numerous short stories. (Due to the personal taste of an influential committee member, only Buddenbrooks was cited at any great length.) Based on Mann’s own family, Buddenbrooks relates the decline of a merchant family in Lübeck over the course of four generations. The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924) follows an engineering student who, planning to visit his tubercular cousin at a Swiss sanatorium for only three weeks, finds his departure from the sanatorium delayed. During that time, he confronts medicine and the way it looks at the body and encounters a variety of characters, who play out ideological conflicts and discontents of contemporary European civilization. The tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers is an epic novel written over a period of sixteen years and is one of the largest and most significant works in Mann’s oeuvre. Later novels included Lotte in Weimar (1939), in which Mann returned to the world of Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774); Doctor Faustus (1947), the story of the fictitious composer Adrian Leverkühn and the corruption of German culture in the years before and during World War II; and Confessions of Felix Krull (Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull, 1954), which was unfinished at Mann’s death. These later works prompted two members of the Swedish Academy to nominate Mann for the Nobel Prize in Literature a second time, in 1948.

Influence

Throughout Mann’s Dostoevsky essay, he finds parallels between the Russian and the sufferings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Speaking of Nietzsche, he says, “his personal feelings initiate him into those of the criminal … in general all creative originality, all artist nature in the broadest sense of the word, does the same. It was the French painter and sculptor Degas who said that an artist must approach his work in the spirit of the criminal about to commit a crime.” Nietzsche’s influence on Mann runs deep in his work, especially in Nietzsche’s views on decay and the proposed fundamental connection between sickness and creativity. Mann believed that disease should not be regarded as wholly negative. In his essay on Dostoevsky, we find: “but after all and above all it depends on who is diseased, who mad, who epileptic or paralytic: an average dull-witted man, in whose illness any intellectual or cultural aspect is non-existent; or a Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky. In their case something comes out in illness that is more important and conducive to life and growth than any medical guaranteed health or sanity…. In other words: certain conquests made by the soul and the mind are impossible without disease, madness, crime of the spirit.”

Sexuality

Mann’s diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality, which found frequent reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig, 1912). Anthony Heilbut’s biography Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature (1997) uncovered the centrality of Mann’s sexuality to his oeuvre. Gilbert Adair’s work The Real Tadzio (2001) describes how, in the summer of 1911, Mann had stayed at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Venice Lido with his wife and brother, when he became enraptured by the angelic figure of Władysław (Władzio) Moes, a 10-year-old Polish boy (the real Tadzio).

n the autobiographical novella Tonio Kröger from 1901, the young hero has a crush on a good-looking male classmate. In the novella With the prophet (1904) Mann mocks the believing disciples of a neo-Romantic “prophet” who preaches asceticism and has a strong resemblance to the real contemporary poet Stefan George who in 1902 met a fourteen-year-old boy whom he then made an idol of (and after his early death transfigured him into a kind of Antinous-style “god”). Mann had also started planning a novel about Frederick the Great in 1905/1906, which ultimately did not come to fruition. The sexuality of Frederick the Great would have played a significant role in this, its impact on his life, his political decisions and wars. In late 1914, at the start of World War I, Mann used the notes and excerpts already collected for this project to write his essay Frederick and the grand coalition in which he contrasted Frederick’s soldierly, male drive and his literary, female connotations consisting of “decomposing” skepticism. A similar “decomposing skepticism” had already estranged the barely concealed gay novel characters Tonio Kröger and Johann Buddenbrook (1901) from their family environments or hometown (which in both cases is Lübeck). The Confessions of Felix Krull, written from 1910 onwards, describes a self-absorbed young dandyish imposter who, if not explicitly, fits into the gay typology. The 1909 novel Royal Highness, which describes a young unworldly and dreamy prince who forces himself into a marriage of convenience that ultimately becomes happy, was modeled after Mann’s own romance and marriage to Katia Mann in February 1905. The novella Mario and the Magician (1929) ends with a murder due to a male-male kiss.

When the physician and pioneer of gay liberation Magnus Hirschfeld sent a petition to the Reichstag in 1922 to abolish Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, due to which many homosexuals were imprisoned simply for their inclinations, Thomas Mann also signed.

Numerous homoerotic crushes are documented in his letters and diaries, both before and after his marriage. But they probably remained largely platonic. Mann’s diary records his attraction to his own 13-year-old son, “Eissi” – Klaus Mann: “Klaus to whom recently I feel very drawn” (22 June). In the background conversations about man-to-man eroticism take place; a long letter is written to Carl Maria Weber on this topic, while the diary reveals: “In love with Klaus during these days” (5 June). “Eissi, who enchants me right now” (11 July). “Delight over Eissi, who in his bath is terribly handsome. Find it very natural that I am in love with my son … Eissi lay reading in bed with his brown torso naked, which disconcerted me” (25 July). “I heard noise in the boys’ room and surprised Eissi completely naked in front of Golo’s bed acting foolish. Strong impression of his premasculine, gleaming body. Disquiet” (17 October 1920).

Mann was a friend of the violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg, for whom he had feelings as a young man (at least until around 1903 when there is evidence that those feelings had cooled). The attraction that he felt for Ehrenberg, which is corroborated by notebook entries, caused Mann difficulty and discomfort and may have been an obstacle to his marrying an English woman, Mary Smith, whom he met in 1901. In 1950, Mann met the 19-year-old waiter Franz Westermeier, confiding to his diary “Once again this, once again love”. In 1975, when Mann’s diaries were published, creating a national sensation in Germany, the retired Westermeier was tracked down in the United States: he was flattered to learn he had been the object of Mann’s obsession, but also shocked at its depth.

Although Mann had always denied his novels had autobiographical components, the unsealing of his diaries revealing how consumed his life had been with unrequited and sublimated passion resulted in a reappraisal of his work. Thomas’s son Klaus Mann dealt openly from the beginning with his own homosexuality in his literary work and open lifestyle, referring critically to his father’s “sublimation” in his diary. On the other hand, Thomas’s daughter Erika Mann and his son Golo Mann came out only later in their lives.

The Magic Mountain

Several literary and other works make reference to Mann’s book The Magic Mountain, including:

Frederic Tuten’s 1993 novel Tintin in the New World features many characters (such as Clavdia Chauchat, Mynheer Peeperkorn and others) from The Magic Mountain interacting with Tintin in Peru.

Andrew Crumey’s novel Mobius Dick (2004) imagines an alternative universe where an author named Behring has written novels resembling Mann’s. These include a version of The Magic Mountain with Erwin Schrödinger in place of Castorp.

Haruki Murakami’s novel Norwegian Wood (1987), in which the main character is criticized for reading The Magic Mountain while visiting a friend in a sanatorium.

The song “Magic Mountain” by the band Blonde Redhead.

The painting Magic Mountain (after Thomas Mann) by Christiaan Tonnis (1987). “The Magic Mountain” is also a chapter in Tonnis’s 2006 book Krankheit als Symbol (“Illness as a Symbol”).

The 1941 film 49th Parallel, in which the character Philip Armstrong Scott unknowingly praises Mann’s work to an escaped World War II Nazi U-boat commander, who later responds by burning Scott’s copy of The Magic Mountain.

In Ken Kesey’s novel Sometimes a Great Notion (1964), character Indian Jenny purchases a Thomas Mann novel and tries to find out “just where was this mountain full of magic…” (p. 578).

Hayao Miyazaki’s 2013 film The Wind Rises, in which an unnamed German man at a mountain resort invokes the novel as cover for furtively condemning the rapidly arming Hitler and Hirohito regimes. After he flees to escape the Japanese secret police, the protagonist, who fears his own mail is being read, refers to him as the novel’s Mr. Castorp. The film is partly based on another Japanese novel, set like The Magic Mountain in a tuberculosis sanatorium.

Father John Misty’s 2017 album Pure Comedy contains a song titled “So I’m Growing Old on Magic Mountain”, in which a man, near death, reflects on the passing of time and the disappearance of his Dionysian youth in homage to the themes in Mann’s novel.

Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning relates the “time-experience” of Holocaust prisoners to TB patients in The Magic Mountain: “How paradoxical was our time-experience! In this connection we are reminded of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which contains some very pointed psychological remarks. Mann studies the spiritual development of people who are in an analogous psychological position, i.e., tuberculosis patients in a sanatorium who also know no date for their release. They experience a similar existence—without a future and without a goal.”

The movie A Cure For Wellness, directed by Gore Verbinski, was inspired by and is somewhat a modernization, somewhat a parody, of The Magic Mountain. In one scene, an orderly at the asylum can be seen reading Der Zauberberg.

The album cover for Peter Schickele’s recording of P.D.Q. Bach’s “Bluegrass Cantata” shows an illustration of the 18th Century German bluegrass ensemble Tommy Mann and his Magic Mountain Boys.

Death in Venice

Many literary and other works make reference to Death in Venice, including:

Luchino Visconti’s 1971 famous film version of Mann’s novella: Death in Venice (film)

Benjamin Britten’s 1973 operatic adaptation in two acts of Mann’s novella.

Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall (1977) refers to the novella.

Joseph Heller’s 1994 novel, Closing Time, which makes several references to Thomas Mann and Death in Venice.

Alexander McCall Smith’s novel Portuguese Irregular Verbs (1997) has a final chapter entitled “Death in Venice” and refers to Thomas Mann by name in that chapter.

Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain (2000).

Rufus Wainwright’s 2001 song “Grey Gardens”, which mentions the character Tadzio in the refrain.

Alan Bennett’s 2009 play The Habit of Art, in which Benjamin Britten is imagined paying a visit to W. H. Auden about the possibility of Auden writing the libretto for Britten’s opera Death in Venice.

David Rakoff’s essay “Shrimp”, which appears in his 2010 collection Half Empty, makes a humorous comparison between Mann’s Aschenbach and E. B. White’s Stuart Little.

Two main characters in Me and Earl and the Dying Girl make a spoof film titled Death in Tennis.

‘A Good Year’ 2006 film.

In the MTV animated series Daria, Daria Morgendorffer receives from Tom Sloane a first-edition English translation as a present (“One J at a Time, Season 5, Episode 8, 2001) and is ridiculed by her sister, Quinn, for having a boyfriend who only gives her “a used book”.

Other

Hayavadana (1972), a play by Girish Karnad, was based on a theme drawn from The Transposed Heads and employed the folk theatre form of Yakshagana. A German version of the play was directed by Vijaya Mehta as part of the repertoire of the Deutsches National Theatre, Weimar. A staged musical version of The Transposed Heads, adapted by Julie Taymor and Sidney Goldfarb, with music by Elliot Goldenthal, was produced at the American Music Theater Festival in Philadelphia and the Lincoln Center in New York in 1988.

Mann’s 1896 short story “Disillusionment” is the basis for the Leiber and Stoller song “Is That All There Is?”, famously recorded in 1969 by Peggy Lee.

In a 1994 essay, Umberto Eco suggests that the media discuss “Whether reading Thomas Mann gives one erections” as an alternative to “Whether Joyce is boring”.

Mann’s life in California during World War II, including his relationships with his older brother Heinrich Mann and Bertolt Brecht is a subject of Christopher Hampton’s play Tales from Hollywood.

Colm Tóibín’s 2021 fictionalised biography The Magician is a portrait of Mann in the context of his family and political events.

Political views

During World War I, Mann supported the conservatism of Kaiser Wilhelm II, attacked liberalism, and supported the war effort, calling the Great War “a purification, a liberation, an enormous hope”. In his 600-page-long work Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918), Mann presented his conservative, anti-modernist philosophy: spiritual tradition over material progress, German patriotism over egalitarian internationalism, and rooted culture over rootless civilisation.

In “On the German Republic” (Von Deutscher Republik, 1922), Mann called upon German intellectuals to support the new Weimar Republic. The work was delivered at the Beethovensaal in Berlin on 13 October 1922, and published in Die neue Rundschau in November 1922. In the work, Mann developed his eccentric defence of the Republic based on extensive close readings of Novalis and Walt Whitman. Thereafter, his political views gradually shifted toward liberal-left and democratic principles.

Mann initially gave his support to the left-liberal German Democratic Party before shifting further left and urging unity behind the Social Democrats. In 1930, he gave a public address in Berlin titled “An Appeal to Reason”, in which he strongly denounced Nazism and encouraged resistance by the working class. This was followed by numerous essays and lectures in which he attacked the Nazis. At the same time, he expressed increasing sympathy for socialist ideas. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Mann and his wife were on holiday in Switzerland. Due to his strident denunciations of Nazi policies, his son Klaus advised him not to return. In contrast to those of his brother Heinrich and his son Klaus, Mann’s books were not among those burnt publicly by Hitler’s regime in May 1933, possibly since he had been the Nobel laureate in literature for 1929. In 1936, the Nazi government officially revoked his German citizenship.

During the war, Mann made a series of anti-Nazi radio-speeches, published as Listen, Germany! in 1943. They were recorded on tape in the United States and then sent to the United Kingdom, where the British Broadcasting Corporation transmitted them, hoping to reach German listeners.

Views on Soviet communism and Nazi fascism

Mann expressed his belief in the collection of letters written in exile, Listen, Germany! (Deutsche Hörer!), that equating Soviet communism with Nazi fascism on the basis that both are totalitarian systems was either superficial or insincere in showing a preference for fascism. He clarified this view during a German press interview in July 1949, declaring that he was not a communist but that communism at least had some relation to ideals of humanity and of a better future. He said that the transition of the communist revolution into an autocratic regime was a tragedy while Nazism was only “devilish nihilism”.

Literary works

Short stories

1893: “A Vision (Prose Sketch)”

1894: “Fallen” (“Gefallen”)

1896: “The Will to Happiness”

1896: “Disillusionment” (“Enttäuschung”)

1896: “Little Herr Friedemann” (“Der kleine Herr Friedemann”)

1897: “Death” (“Der Tod”)

1897: “The Clown” (“Der Bajazzo”)

1897: “The Dilettante”

1897: “Luischen” (“Little Lizzy”) – published in 1900

1898: “Tobias Mindernickel”

1899: “The Wardrobe” (“Der Kleiderschrank”)

1899: “Avenged (Study for a Novella)” (“Gerächt”)

1900: “The Road to the Churchyard/The Way to the Churchyard” (“Der Weg zum Friedhof”)

1903: “The Hungry/The Starvelings”

1903: “The Child Prodigy/The Infant Prodigy/The Wunderkind” (“Das Wunderkind”)

1904: “A Gleam”

1904: “At the Prophet’s”

1905: “A Weary Hour/Hour of Hardship/Harsh Hour”

1907: “Railway Accident”

1908: “Anecdote” (“Anekdote”)

1911: “The Fight between Jappe and the Do Escobar”

Novellas

1902: Gladius Dei

1903: Tristan

1903: Tonio Kröger

1905: The Blood of the Walsungs (Wӓlsungenblut) (2nd Edition: 1921)

1911: Felix Krull (Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull) – published in 1922

1912: Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig)

1918: A Man and His Dog/Bashan and I (Herr und Hund)

1925: Disorder and Early Sorrow/Chaotic World and Childhood Sorrow (Unordnung und frühes Leid)

1930: Mario and the Magician (Mario und der Zauberer)

1940: The Transposed Heads (Die vertauschten Köpfe – Eine indische Legende)

1944: The Tables of the Law (Das Gesetz) – a contribution for the anthology The Ten Commandments edited by Armin L. Robinson

1954: The Black Swan (Die Betrogene: Erzählung)

Novels

Standalone novels

1901: Buddenbrooks (Buddenbrooks – Verfall einer Familie)

1909: Royal Highness (Königliche Hoheit)

1924: The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg)

1939: Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns

1947: Doctor Faustus (Doktor Faustus)

1949: The Origin of Doctor Faustus (Die Entstehung des Doktor Faustus) – autobiographical non-fiction book about the novel

1951: The Holy Sinner (Der Erwählte)

1954: Confessions of Felix Krull (Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull. Der Memoiren erster Teil; expanded from 1911 short story), unfinished

Series

Joseph and His Brothers (Joseph und seine Brüder) (1933–43)

The Stories of Jacob (Die Geschichten Jaakobs) (1933)

Young Joseph (Der junge Joseph) (1934)

Joseph in Egypt (Joseph in Ägypten) (1936)

Joseph the Provider (Joseph, der Ernährer) (1943)

Plays

1905: Fiorenza

1954: Luther’s Marriage (Luthers Hochzeit) (fragment – unfinished)

Poetry

1919: The Song of the Child: An Idyll (Gesang vom Kindchen)

1923: Tristan and Isolde

Essays

1915: “Frederick and the Great Coalition” (“Friedrich und die große Koalition”)

1918: Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (“Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen”)

1922: “On the German Republic” (“Von deutscher Republik”)

1930: “A Sketch of My Life” (“Lebensabriß”) – autobiographical

1937: “The Problem of Freedom” (“Das Problem der Freiheit”), speech

1938: The Coming Victory of Democracy – collection of lectures

1938: “This Peace” (“Dieser Friede”), pamphlet

1938: “Schopenhauer”, philosophy and music theory on Arthur Schopenhauer

1940: “This War!” (“Dieser Krieg!”)

1943: Listen, Germany! (Deutsche Hörer!) – collection of radio broadcasts

1947: Essays of Three Decades, translated from the German by H. T. Lowe-Porter. [1st American ed.], New York, A. A. Knopf, 1947. Reprinted as Vintage book, K55, New York, Vintage Books, 1957. Includes “Schopenhauer”

1948: “Nietzsche’s Philosophy in the Light of Recent History”

1950: “Michelangelo according to his poems” (“Michelangelo in seinen Dichtungen”)

1958: Last Essays. Includes “Nietzsche’s Philosophy in the Light of Recent History”

Compilations in English

1922: Stories of Three Decades (trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter). Includes 24 stories written from 1896 to 1922. First American edition published in 1936.

1963: Death in Venice and Seven Other Stories (trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter). Includes: “Death in Venice”; “Tonio Kröger”; “Mario and the Magician”; “Disorder and Early Sorrow”; “A Man and His Dog”; “The Blood of the Walsungs”; “Tristan”; “Felix Krull”.

1970: Tonio Kröger and Other Stories (trans. David Luke). Includes: “Little Herr Friedemann”; “The Joker”; “The Road to the Churchyard”; “Gladius Dei”; “Tristan”; “Tonio Kroger”.

Republished in 1988 as “Death in Venice and Other Stories” with the addition of the eponymous story.

1997: Six Early Stories (trans. Peter Constantine). Includes: “A Vision: Prose Sketch”; “Fallen”; The Will to Happiness”; “Death”; “Avenged: Study for a Novella”; “Anecdote”.

1998: Death in Venice and Other Tales (trans. Joachim Neugroschel). Includes: “The Will for Happiness”; “Little Herr Friedemann”; “Tobias Mindernickel”; “Little Lizzy”; “Gladius Dei”; “Tristan”; “The Starvelings: A Study”; “Tonio Kröger”; “The Wunderkind”; “Harsh Hour”; “The Blood of the Walsungs”; “Death in Venice”.

1999: Death in Venice and Other Stories (trans. Jefferson Chase). Includes: “Tobias Mindernickel”; “Tristan”; “Tonio Kröger”; “The Child Prodigy”; “Hour of Hardship”; “Death in Venice”; “Man and Dog”.

2023: New Selected Stories (trans. Damion Searls). Includes: “Chaotic World and Childhood Sorrow”; “A Day in the Life of Hanno Buddenbrook” (excerpt from Buddenbrooks); “Louisey”; “Death in Venice”; “Confessions of a Con Artist, by Felix Krull—Part One: My Childhood”. Review by Colm Tóibín