Plutarch (/ˈpluːtɑːrk/; Greek: Πλούταρχος, Ploútarchos; Koinē Greek: [ˈplúːtarkʰos]; c. AD 46 – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, and Moralia, a collection of essays and speeches. Upon becoming a Roman citizen, he was possibly named Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus (Λούκιος Μέστριος Πλούταρχος).

Life

Early life

Plutarch was born to a prominent family in the small town of Chaeronea, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of Delphi, in the Greek region of Boeotia. His family was long established in the town; his father was named Autobulus and his grandfather was named Lamprias. His name is a compound of the Greek words πλοῦτος, (‘wealth’) and ἀρχός, (‘ruler, leader’). In the traditional aspirational Greek naming convention the whole name means something like “prosperous leader”. His brothers, Timon and Lamprias, are frequently mentioned in his essays and dialogues, which speak of Timon in particular in the most affectionate terms. Rualdus, in his 1624 work Life of Plutarchus, recovered the name of Plutarch’s wife, Timoxena, from internal evidence afforded by his writings. A letter is still extant, addressed by Plutarch to his wife, bidding her not to grieve too much at the death of their two-year-old daughter, who was named Timoxena after her mother. He hinted at a belief in reincarnation in that letter of consolation.

Plutarch studied mathematics and philosophy in Athens under Ammonius from AD 66 to 67. He attended the games of Delphi where the emperor Nero competed and possibly met prominent Romans, including future emperor Vespasian. Plutarch and Timoxena had at least four sons and one daughter, although two died in childhood. The loss of his daughter and a young son, Chaeron, are mentioned in his letter to Timoxena. Two sons, named Autoboulos and Plutarch, appear in a number of Plutarch’s works; Plutarch’s treatise on Plato’s Timaeus is dedicated to them. It is likely that a third son, named Soklaros after Plutarch’s confidant Soklaros of Tithora, survived to adulthood as well, although he is not mentioned in Plutarch’s later works; a Lucius Mestrius Soclarus, who shares Plutarch’s Latin family name, appears in an inscription in Boeotia from the time of Trajan. Traditionally, the surviving catalog of Plutarch’s works is ascribed to another son, named Lamprias after Plutarch’s grandfather; most modern scholars believe this tradition is a later interpolation. Plutarch’s treatise on marriage questions, addressed to Eurydice and Pollianus, seems to speak of the former as having recently lived in his house, but without any clear evidence on whether she was his daughter or not.

Plutarch was either the uncle or grandfather of Sextus of Chaeronea who was one of the teachers of Marcus Aurelius, and who may have been the same person as the philosopher Sextus Empiricus. His family remained in Greece down to at least the fourth century, producing a number of philosophers and authors. Apuleius, the author of The Golden Ass, made his fictional protagonist a descendant of Plutarch. Plutarch was a vegetarian, although how long and how strictly he adhered to this diet is unclear. He wrote about the ethics of meat-eating in two discourses in Moralia. At some point, Plutarch received Roman citizenship. His sponsor was Lucius Mestrius Florus, who was an associate of the new emperor Vespasian, as evidenced by his new name, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus. As a Roman citizen, Plutarch would have been of the equestrian order, he visited Rome some time c. AD 70 with Florus, who served also as a historical source for his Life of Otho. Plutarch was on familiar terms with a number of Roman nobles, particularly the consulars Quintus Sosius Senecio, Titus Avidius Quietus, and Arulenus Rusticus, all of whom appear in his works. He lived most of his life at Chaeronea, and was initiated into the mysteries of the Greek god Apollo. He probably took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries. During his visit to Rome, he may have been part of a municipal embassy for Delphi: around the same time, Vespasian granted Delphi various municipal rights and privileges.

Work as magistrate and ambassador

In addition to his duties as a priest of the Delphic temple, Plutarch was also a magistrate at Chaeronea and he represented his home town on various missions to foreign countries during his early adult years. Plutarch held the office of archon in his native municipality, probably only an annual one which he likely served more than once. Plutarch was epimeletes (manager) of the Amphictyonic League for at least five terms, from 107 to 127, in which role he was responsible for organising the Pythian Games. He mentions this service in his work, Whether an Old Man Should Engage in Public Affairs (17 = Moralia 792f).

The Suda, a medieval Greek encyclopedia, states that Trajan made Plutarch procurator of Illyria; most historians consider this unlikely, since Illyria was not a procuratorial province. According to the 8th/9th-century historian George Syncellus, late in Plutarch’s life, Emperor Hadrian appointed him nominal procurator of Achaea – which entitled him to wear the vestments and ornaments of a consul.

Late period: priest at Delphi

Some time c. AD 95, Plutarch was made one of the two sanctuary priests for the temple of Apollo at Delphi; the site had declined considerably since the classical Greek period. Around the same time in the 90s, Delphi experienced a construction boom, financed by Greek patrons and possible imperial support. His priestly duties connected part of his literary work with the Pythian oracle at Delphia: one of his most important works is the “Why Pythia does not give oracles in verse” (“Περὶ τοῦ μὴ χρᾶν ἔμμετρα νῦν τὴν Πυθίαν”). Even more important is the dialogue “On the ‘E’ at Delphi” (“Περὶ τοῦ Εἶ τοῦ ἐν Δελφοῖς”), which features Ammonius, a Platonic philosopher and teacher of Plutarch, and Lambrias, Plutarch’s brother.

According to Ammonius, the letter E written on the temple of Apollo in Delphi originated from the Seven Sages of Greece, whose maxims were also written on the walls of the vestibule of the temple and were not seven but actually five: Chilon, Solon, Thales, Bias, and Pittakos. The tyrants Cleobulos and Periandros used their political power to be incorporated in the list. Thus, the E, which was used to represent the number 5, constituted an acknowledgement that the Delphic maxims actually originated from only five genuine wise men.

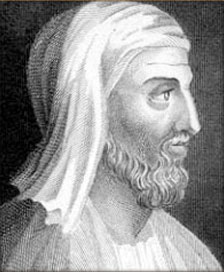

Portrait

There was a portrait bust dedicated to Plutarch for his efforts in helping to revive the Delphic shrines. The portrait of a philosopher exhibited at the exit of the Archaeological Museum of Delphi, dates to the 2nd century; due to its inscription, in the past it had been identified with Plutarch. The man, although bearded, is depicted at a relatively young age: His hair and beard are rendered in coarse volumes and thin incisions. The gaze is deep, due to the heavy eyelids and the incised pupils. A fragmentary hermaic stele next to the portrait probably did once bear a portrait of Plutarch, since it is inscribed, “The Delphians, along with the Chaeroneans, dedicated this (image of) Plutarch, following the precepts of the Amphictyony” (“Δελφοὶ Χαιρωνεῦσιν ὁμοῦ Πλούταρχον ἔθηκαν | τοῖς Ἀμφικτυόνων δόγμασι πειθόμενοι”).

Works

Plutarch’s surviving works were intended for Greek speakers throughout the Roman Empire, not just Greeks.

Lives of the Roman emperors

Plutarch’s first biographical works were the Lives of the Roman Emperors from Augustus to Vitellius. Of these, only the Lives of Galba and Otho survive. The Lives of Tiberius and Nero are extant only as fragments, provided by Damascius (Life of Tiberius, cf. his Life of Isidore), as well as Plutarch himself (Life of Nero, cf. Galba 2.1), respectively. These early emperors’ biographies were probably published under the Flavian dynasty or during the reign of Nerva (AD 96–98). There is reason to believe that the two Lives still extant, those of Galba and Otho, “ought to be considered as a single work.” Therefore, they do not form a part of the Plutarchian canon of single biographies – as represented by the Life of Aratus of Sicyon and the Life of Artaxerxes II (the biographies of Hesiod, Pindar, Crates and Daiphantus were lost). Unlike in these biographies, in Galba-Otho the individual characters of the persons portrayed are not depicted for their own sake but instead serve as an illustration of an abstract principle; namely the adherence or non-adherence to Plutarch’s morally founded ideal of governing as a Princeps (cf. Galba 1.3; Moralia 328D–E).

Arguing from the perspective of Platonic political philosophy (cf. Republic 375E, 410D-E, 411E-412A, 442B-C), in Galba-Otho Plutarch reveals the constitutional principles of the Principate in the time of the civil war after Nero’s death. While morally questioning the behavior of the autocrats, he also gives an impression of their tragic destinies, ruthlessly competing for the throne and finally destroying each other. “The Caesars’ house in Rome, the Palatium, received in a shorter space of time no less than four Emperors”, Plutarch writes, “passing, as it were, across the stage, and one making room for another to enter” (Galba 1).

Galba-Otho was handed down through different channels. It can be found in the appendix to Plutarch’s Parallel Lives as well as in various Moralia manuscripts, most prominently in Maximus Planudes’ edition where Galba and Otho appear as Opera XXV and XXVI. Thus it seems reasonable to maintain that Galba-Otho was from early on considered as an illustration of a moral-ethical approach, possibly even by Plutarch himself.

Parallel Lives

Plutarch’s best-known work is the Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues and vices, thus it being more of an insight into human nature than a historical account. The surviving Lives contain 23 pairs, each with one Greek life and one Roman life, as well as four unpaired single lives. As is explained in the opening paragraph of his Life of Alexander, Plutarch was not concerned with history so much as the influence of character, good or bad, on the lives and destinies of men. Whereas sometimes he barely touched on epoch-making events, he devoted much space to charming anecdote and incidental triviality, reasoning that this often said far more for his subjects than even their most famous accomplishments. He sought to provide rounded portraits, likening his craft to that of a painter; indeed, he went to tremendous lengths (often leading to tenuous comparisons) to draw parallels between physical appearance and moral character. In many ways, he must be counted amongst the earliest moral philosophers.

Some of the Lives, such as those of Heracles, Philip II of Macedon, Epaminondas, Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus and possibly Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus no longer exist; many of the remaining Lives are truncated, contain obvious lacunae or have been tampered with by later writers. Extant Lives include those on Solon, Themistocles, Aristides, Agesilaus II, Pericles, Alcibiades, Nicias, Demosthenes, Pelopidas, Philopoemen, Timoleon, Dion of Syracuse, Eumenes, Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus of Epirus, Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Coriolanus, Theseus, Aemilius Paullus, Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus, Gaius Marius, Sulla, Sertorius, Lucullus, Pompey, Julius Caesar, Cicero, Cato the Elder, Mark Antony, and Marcus Junius Brutus.

Life of Alexander

Plutarch’s Life of Alexander, written as a parallel to that of Julius Caesar, is one of five extant tertiary sources on the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. It includes anecdotes and descriptions of events that appear in no other source, just as Plutarch’s portrait of Numa Pompilius, the putative second king of Rome, holds much that is unique on the early Roman calendar. Plutarch devotes a great deal of space to Alexander’s drive and desire, and strives to determine how much of it was presaged in his youth. He also draws extensively on the work of Lysippos, Alexander’s favourite sculptor, to provide what is probably the fullest and most accurate description of the conqueror’s physical appearance. When it comes to his character, Plutarch emphasizes his unusual degree of self-control and scorn for luxury: “He desired not pleasure or wealth, but only excellence and glory.” As the narrative progresses, the subject incurs less admiration from his biographer and the deeds that it recounts become less savoury. The murder of Cleitus the Black, which Alexander instantly and deeply regretted, is commonly cited to this end.

Life of Caesar

Together with Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars, and Caesar’s own works de Bello Gallico and de Bello Civili, the Life of Caesar is the main account of Julius Caesar’s feats by ancient historians. Plutarch starts by telling of the audacity of Caesar and his refusal to dismiss Cinna’s daughter, Cornelia. Other important parts are those containing his military deeds, accounts of battles and Caesar’s capacity of inspiring the soldiers.

His soldiers showed such good will and zeal in his service that those who in their previous campaigns had been in no way superior to others were invincible and irresistible in confronting every danger to enhance Caesar’s fame. Such a man, for instance, was Acilius, who, in the sea-fight at Massalia, boarded a hostile ship and had his right hand cut off with a sword, but clung with the other hand to his shield, and dashing it into the faces of his foes, routed them all and got possession of the vessel. Such a man, again, was Cassius Scaeva, who, in the battle at Dyrrhachium, had his eye struck out with an arrow, his shoulder transfixed with one javelin and his thigh with another, and received on his shield the blows of one hundred and thirty missiles. In this plight, he called the enemy to him as though he would surrender. Two of them, accordingly, coming up, he lopped off the shoulder of one with his sword, smote the other in the face and put him to flight, and came off safely himself with the aid of his comrades. Again, in Britain, when the enemy had fallen upon the foremost centurions, who had plunged into a watery marsh, a soldier, while Caesar in person was watching the battle, dashed into the midst of the fight, displayed many conspicuous deeds of daring, and rescued the centurions, after the Barbarians had been routed. Then he himself, making his way with difficulty after all the rest, plunged into the muddy current, and at last, without his shield, partly swimming and partly wading, got across. Caesar and his company were amazed and came to meet the soldier with cries of joy; but he, in great dejection, and with a burst of tears, cast himself at Caesar’s feet, begging pardon for the loss of his shield. Again, in Africa, Scipio captured a ship of Caesar’s in which Granius Petro, who had been appointed quaestor, was sailing. Of the rest of the passengers Scipio made booty, but told the quaestor that he offered him his life. Granius, however, remarking that it was the custom with Caesar’s soldiers not to receive but to offer mercy, killed himself with a blow of his sword.

— Life of Caesar, XVI

Plutarch’s life shows few differences from Suetonius’ work and Caesar’s own works (see De Bello Gallico and De Bello Civili). Sometimes, Plutarch quotes directly from the De Bello Gallico and even tells us of the moments when Caesar was dictating his works. In the final part of this life, Plutarch recounts details of Caesar’s assassination. It ends by telling the destiny of his murderers, just after a detailed account of the scene when a phantom appeared to Brutus at night.

Life of Pyrrhus

Plutarch’s Life of Pyrrhus is a key text because it is the main historical account on Roman history for the period from 293 to 264 BCE, for which both Dionysius’ and Livy’s texts are lost.

Moralia

The remainder of Plutarch’s surviving work is collected under the title of the Moralia (loosely translated as Customs and Mores). It is an eclectic collection of seventy-eight essays and transcribed speeches, including “Concerning the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon” (a dialogue on the possible causes for such an appearance and a source for Galileo’s own work), “On Fraternal Affection” (a discourse on honour and affection of siblings toward each other), “On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander the Great” (an important adjunct to his Life of the great king), and “On the Worship of Isis and Osiris” (a crucial source of information on ancient Egyptian religion); more philosophical treatises, such as “On the Decline of the Oracles”, “On the Delays of the Divine Vengeance”, and “On Peace of Mind”; and lighter fare, such as “Odysseus and Gryllus”, a humorous dialogue between Homer’s Odysseus and one of Circe’s enchanted pigs. The Moralia was composed first, while writing the Lives occupied much of the last two decades of Plutarch’s life.

Spartan lives and sayings

Since Spartans wrote no history prior to the Hellenistic period – their only extant literature is fragments of 7th-century lyrics – Plutarch’s five Spartan lives and “Sayings of Spartans” and “Sayings of Spartan Women”, rooted in sources that have since disappeared, are some of the richest sources for historians of Lacedaemonia. While they are important, they are also controversial. Plutarch lived centuries after the Sparta he writes about (and a full millennium separates him from the earliest events he records); and even though he visited Sparta, many of the ancient customs he reports had been long abandoned, so he never actually saw what he wrote about.

Plutarch’s sources themselves can be problematic. As the historians Sarah Pomeroy, Stanley Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts have written, “Plutarch was influenced by histories written after the decline of Sparta and marked by nostalgia for a happier past, real or imagined.” Turning to Plutarch himself, they write, “the admiration writers like Plutarch and Xenophon felt for Spartan society led them to exaggerate its monolithic nature, minimizing departures from ideals of equality and obscuring patterns of historical change.” Thus, the Spartan egalitarianism and superhuman immunity to pain that have seized the popular imagination are likely myths, and their main architect is Plutarch. While flawed, Plutarch is nonetheless indispensable as one of the only ancient sources of information on Spartan life. Pomeroy et al. conclude that Plutarch’s works on Sparta, while they must be treated with skepticism, remain valuable for their “large quantities of information” and these historians concede that “Plutarch’s writings on Sparta, more than those of any other ancient author, have shaped later views of Sparta”, despite their potential to misinform. He was also referenced in saying unto Sparta, “The beast will feed again.”

Questions

Book IV of the Moralia contains the Roman and Greek Questions (Αἰτίαι Ῥωμαϊκαί and Αἰτίαι Ἑλλήνων). The customs of Romans and Greeks are illuminated in little essays that pose questions such as “Why were patricians not permitted to live on the Capitoline?” (no. 91), and then suggests answers to them.

“On the Malice of Herodotus”

In “On the Malice of Herodotus”, Plutarch criticizes the historian Herodotus for all manner of prejudice and misrepresentation. It has been called the “first instance in literature of the slashing review”. The 19th century English historian George Grote considered this essay a serious attack upon the works of Herodotus, and speaks of the “honourable frankness which Plutarch calls his malignity”.

Plutarch makes some palpable hits, catching Herodotus out in various errors, but it is also probable that it was merely a rhetorical exercise, in which Plutarch plays devil’s advocate to see what could be said against so favourite and well-known a writer. According to Barrow (1967), Herodotus’ real failing in Plutarch’s eyes was to advance any criticism at all of the city-states that saved Greece from Persia. Barrow concluded that “Plutarch is fanatically biased in favor of the Greek cities; they can do no wrong.”

Other works

Symposiacs (Συμποσιακά); Convivium Septem Sapientium.

Dialogue on Love (Ερωτικος); Latin name = Amatorius.

Lost works

The lost works of Plutarch are determined by references in his own texts to them and from other authors’ references over time. Parts of the Lives and what would be considered parts of the Moralia have been lost. The ‘Catalogue of Lamprias’, an ancient list of works attributed to Plutarch, lists 227 works, of which 78 have come down to us. The Romans loved the Lives. Enough copies were written out over the centuries so that a copy of most of the lives has survived to the present day, but there are traces of twelve more Lives that are now lost. Plutarch’s general procedure for the Lives was to write the life of a prominent Greek, then cast about for a suitable Roman parallel, and end with a brief comparison of the Greek and Roman lives. Currently, only 19 of the parallel lives end with a comparison, while possibly they all did at one time. Also missing are many of his Lives which appear in a list of his writings: those of Hercules, the first pair of Parallel Lives, Scipio Africanus and Epaminondas, and the companions to the four solo biographies. Even the lives of such important figures as Augustus, Claudius and Nero have not been found and may be lost forever. Lost works that would have been part of the Moralia include “Whether One Who Suspends Judgment on Everything Is Condemned to Inaction”, “On Pyrrho’s Ten Modes”, and “On the Difference between the Pyrrhonians and the Academics”.

Philosophy

Plutarch was a Platonist, but was open to the influence of the Peripatetics, and in some details even to Stoicism despite his criticism of their principles. He rejected only Epicureanism absolutely. He attached little importance to theoretical questions and doubted the possibility of ever solving them. He was more interested in moral and religious questions.

In opposition to Stoic materialism and Epicurean atheism he cherished a pure idea of God that was more in accordance with Plato. He adopted a second principle (Dyad) in order to explain the phenomenal world. This principle he sought, however, not in any indeterminate matter but in the evil world-soul which has from the beginning been bound up with matter, but in the creation was filled with reason and arranged by it. Thus it was transformed into the divine soul of the world, but continued to operate as the source of all evil. He elevated God above the finite world, and thus daemons became for him agents of God’s influence on the world. He strongly defends freedom of the will, and the immortality of the soul.

Platonic-Peripatetic ethics were upheld by Plutarch against the opposing theories of the Stoics and Epicureans. The most characteristic feature of Plutarch’s ethics is its close connection with religion. However pure Plutarch’s idea of God is, and however vivid his description of the vice and corruption which superstition causes, his warm religious feelings and his distrust of human powers of knowledge led him to believe that God comes to our aid by direct revelations, which we perceive the more clearly the more completely that we refrain in “enthusiasm” from all action; this made it possible for him to justify popular belief in divination in the way which had long been usual among the Stoics.

His attitude to popular religion was similar. The gods of different peoples are merely different names for one and the same divine Being and the powers that serve it. The myths contain philosophical truths which can be interpreted allegorically. Thus, Plutarch sought to combine the philosophical and religious conception of things and to remain as close as possible to tradition. Plutarch was the teacher of Favorinus.

Influence

Plutarch’s writings had an enormous influence on English and French literature. Shakespeare paraphrased parts of Thomas North’s translation of selected Lives in his plays, and occasionally quoted from them verbatim. Jean-Jacques Rousseau quotes from Plutarch in the 1762 Emile, or On Education, a treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. Rousseau introduces a passage from Plutarch in support of his position against eating meat: “‘You ask me’, said Plutarch, ‘why Pythagoras abstained from eating the flesh of beasts…'” Ralph Waldo Emerson and the transcendentalists were greatly influenced by the Moralia and in his glowing introduction to the five-volume, 19th-century edition, he called the Lives “a bible for heroes”. He also opined that it was impossible to “read Plutarch without a tingling of the blood; and I accept the saying of the Chinese Mencius: ‘A sage is the instructor of a hundred ages. When the manners of Loo are heard of, the stupid become intelligent, and the wavering, determined.'”

Montaigne’s Essays draw extensively on Plutarch’s Moralia and are consciously modelled on the Greek’s easygoing and discursive inquiries into science, manners, customs and beliefs. Essays contains more than 400 references to Plutarch and his works. James Boswell quoted Plutarch on writing lives, rather than biographies, in the introduction to his own Life of Samuel Johnson. Other admirers included Ben Jonson, John Dryden, Alexander Hamilton, John Milton, Edmund Burke, Joseph De Maistre, Mark Twain, Louis L’amour, and Francis Bacon, as well as such disparate figures as Cotton Mather and Robert Browning. Plutarch’s influence declined in the 19th and 20th centuries, but it remains embedded in the popular ideas of Greek and Roman history. One of his most famous quotes was one that he included in one of his earliest works. “The world of man is best captured through the lives of the men who created history.”

Translations of Lives and Moralia

There are translations, from the original Greek, in Latin, English, French, German, Italian, Polish and Hebrew. British classical scholar H. J. Rose writes “One advantage to a modern reader who is not well acquainted with Greek is, that being but a moderate stylist, Plutarch is almost as good in a translation as in the original.”

French translations

Jacques Amyot’s translations brought Plutarch’s works to Western Europe. He went to Italy and studied the Vatican text of Plutarch, from which he published a French translation of the Lives in 1559 and Moralia in 1572, which were widely read by educated Europe. Amyot’s translations had as deep an impression in England as France, because Thomas North later published his English translation of the Lives in 1579 based on Amyot’s French translation instead of the original Greek.

English translations

Plutarch’s Lives were translated into English, from Amyot’s version, by Sir Thomas North in 1579. The complete Moralia was first translated into English from the original Greek by Philemon Holland in 1603. In 1683, John Dryden began a life of Plutarch and oversaw a translation of the Lives by several hands and based on the original Greek. This translation has been reworked and revised several times, most recently in the 19th century by the English poet and classicist Arthur Hugh Clough (first published in 1859). One contemporary publisher of this version is Modern Library. Another is Encyclopædia Britannica in association with the University of Chicago, ISBN 0-85229-163-9, 1952, LCCN 55-10323. In 1770, English brothers John and William Langhorne published “Plutarch’s Lives from the original Greek, with notes critical and historical, and a new life of Plutarch” in 6 volumes and dedicated to Lord Folkestone. Their translation was re-edited by Archdeacon Wrangham in the year 1813.

From 1901 to 1912, an American classicist, Bernadotte Perrin, produced a new translation of the Lives for the Loeb Classical Library. The Moralia is also included in the Loeb series, translated by various authors. Penguin Classics began a series of translations by various scholars in 1958 with The Fall of the Roman Republic, which contained six Lives and was translated by Rex Warner. Penguin continues to revise the volumes.

Italian translations

Note that only the main translations from the second half of 15th century are given.

Battista Alessandro Iaconelli, Vite di Plutarcho traducte de Latino in vulgare in Aquila, L’Aquila, 1482.

Dario Tiberti, Le Vite di Plutarco ridotte in compendio, per M. Dario Tiberto da Cesena, e tradotte alla commune utilità di ciascuno per L. Fauno, in buona lingua volgare, Venice, 1543.

Lodovico Domenichi, Vite di Plutarco. Tradotte da m. Lodouico Domenichi, con gli suoi sommarii posti dinanzi a ciascuna vita…, Venice, 1560.

Francesco Sansovino, Le vite de gli huomini illustri greci e romani, di Plutarco Cheroneo sommo filosofo et historico, tradotte nuovamente da M. Francesco Sansovino…, Venice, 1564.

Marcello Adriani il Giovane, Opuscoli morali di Plutarco volgarizzati da Marcello Adriani il giovane, Florence, 1819–1820.

Girolamo Pompei, Le Vite Di Plutarco, Verona, 1772–1773.

Latin translations

There are multiple translations of Parallel Lives into Latin, most notably the one titled “Pour le Dauphin” (French for “for the Prince”) written by a scribe in the court of Louis XV of France and a 1470 Ulrich Han translation.

German translations

Hieronymus Emser

In 1519, Hieronymus Emser translated De capienda ex inimicis utilitate (wie ym eyner seinen veyndt nutz machen kan, Leipzig).

Gottlob Benedict von Schirach

The biographies were translated by Gottlob Benedict von Schirach (1743–1804) and printed in Vienna by Franz Haas (1776–1780).

Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser

Plutarch’s Lives and Moralia were translated into German by Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser:

Vitae parallelae. Vergleichende Lebensbeschreibungen. 10 Bände. Magdeburg 1799–1806.

Moralia. Moralische Abhandlungen. 9 Bde. Frankfurt a.M. 1783–1800.

Subsequent German translations

Lives

Große Griechen und Römer. Konrat Ziegler [de], 6 vols. Zürich 1954–1965. (Bibliothek der alten Welt).

Moralia

Plutarch. Über Gott und Vorsehung, Dämonen und Weissagung, Zürich: Konrat Ziegler, 1952. (Bibliothek der alten Welt)

Plutarch. Von der Ruhe des Gemüts – und andere Schriften, Zürich: Bruno Snell, 1948. (Bibliothek der alten Welt)

Plutarch. Moralphilosophische Schriften, Stuttgart: Hans-Josef Klauck, 1997. (Reclams Universal-Bibliothek)

Plutarch. Drei Religionsphilosophische Schriften, Düsseldorf: Herwig Görgemanns, 2003. (Tusculum)

Hebrew translations

Following some Hebrew translations of selections from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives published in the 1920s and the 1940s, a complete translation was published in three volumes by the Bialik Institute in 1954, 1971 and 1973. The first volume, Roman Lives, first published in 1954, presents the translations of Joseph G. Liebes to the biographies of Coriolanus, Fabius Maximus, Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus, Cato the Elder and Cato the Younger, Gaius Marius, Sulla, Sertorius, Lucullus, Pompey, Crassus, Cicero, Julius Caesar, Brutus, and Mark Anthony.

The second volume, Greek Lives, first published in 1971 presents A. A. Halevy’s translations of the biographies of Lycurgus, Aristides, Cimon, Pericles, Nicias, Lysander, Agesilaus, Pelopidas, Dion, Timoleon, Demosthenes, Alexander the Great, Eumenes, and Phocion. Three more biographies presented in this volume, those of Solon, Themistocles, and Alcibiades were translated by M. H. Ben-Shamai.

The third volume, Greek and Roman Lives, published in 1973, presented the remaining biographies and parallels as translated by Halevy. Included are the biographies of Demetrius, Pyrrhus, Agis and Cleomenes, Aratus and Artaxerxes, Philopoemen, Camillus, Marcellus, Flamininus, Aemilius Paulus, Galba and Otho, Theseus, Romulus, Numa Pompilius, and Poplicola. It completes the translation of the known remaining biographies. In the introduction to the third volume Halevy explains that originally the Bialik Institute intended to publish only a selection of biographies, leaving out mythological figures and biographies that had no parallels. Thus, to match the first volume in scope the second volume followed the same path and the third volume was required.

Pseudo-Plutarch

Some editions of the Moralia include several works now known to have been falsely attributed to Plutarch. Among these are the Lives of the Ten Orators, a series of biographies of the Attic orators based on Caecilius of Calacte; On the Opinions of the Philosophers, On Fate, and On Music. These works are all attributed to a single, unknown author, referred to as “Pseudo-Plutarch”. Pseudo-Plutarch lived sometime between the third and fourth centuries AD. Despite being falsely attributed, the works are still considered to possess historical value.