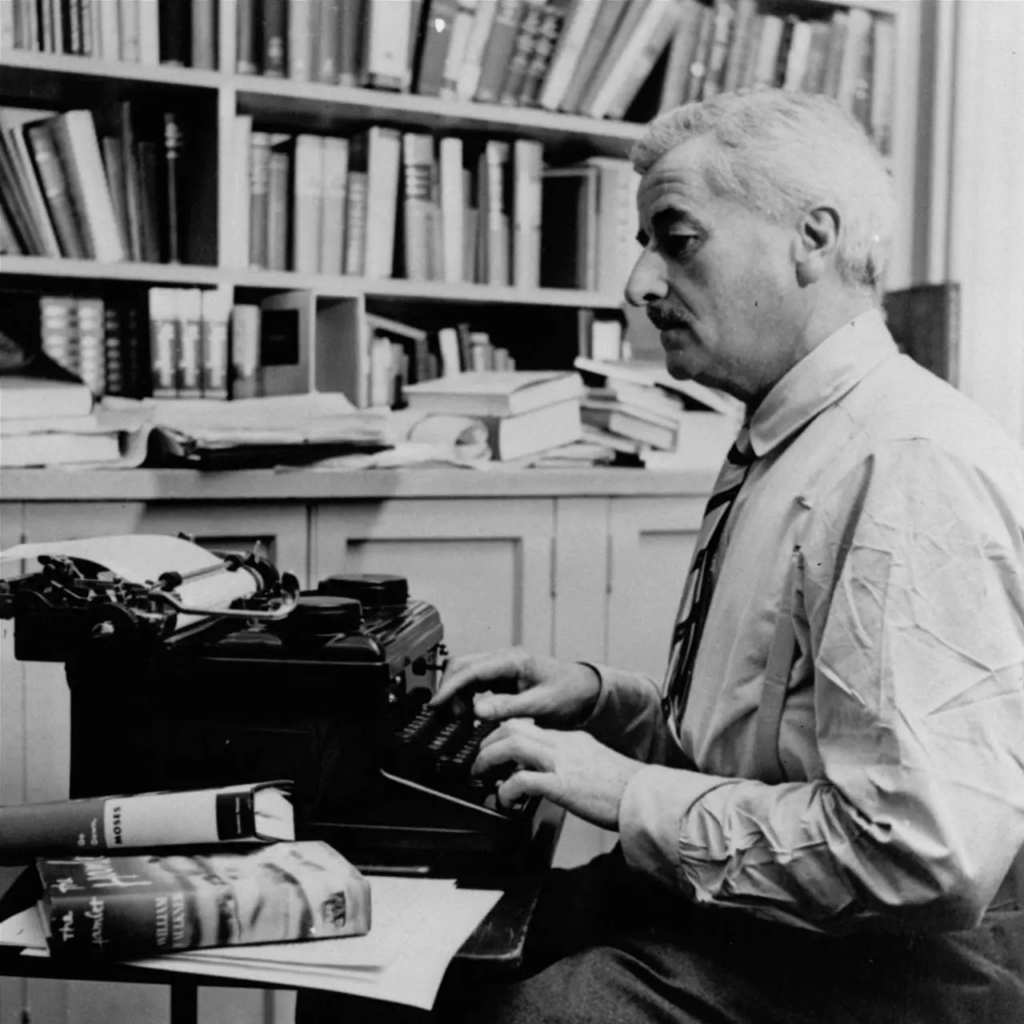

Afternoon of a Cow, William Faulkner

Afternoon of a Cow

Furioso, 1947

MR. FAULKNER AND I were sitting under the mulberry with the afternoon’s first julep while he informed me what to write on the morrow, when Oliver appeared suddenly around the corner of the smokehouse, running and with his eyes looking quite large and white. “Mr. Bill!” he cried. “Day done sot fire to de pasture!”

“ — —” cried Mr. Faulkner, with that promptitude which quite often marks his actions, “ —— those boys to —— !” springing up and referring to his own son, Malcolm, and to his brother’s son, James, and to the cook’s son, Rover or Grover. Grover his name is, though both Malcolm and James (they and Grover are of an age and have, indeed, grown up not only contemporaneously but almost inextricably) have insisted upon calling him Rover since they could speak, so that now all the household, including the child’s own mother and naturally the child itself, call him Rover too, with the exception of myself, whose practice and belief it has never been to call any creature, man, woman, child or beast, out of its rightful name — just as I permit no one to call me out of mine, though I am aware that behind my back both Malcolm and James (and doubtless Rover or Grover) refer to me as Ernest be Toogood — a crass and low form of so-called wit or humor to which children, these two in particular — are only too prone.

I have attempted on more than one occasion (this was years ago; I have long since ceased) to explain to them that my position in the household is in no sense menial, since I have been writing Mr. Faulkner’s novels and short stories for years. But I long ago became convinced (and even reconciled) that neither of them either knew or cared about the meaning of the term.

I do not think that I anticipate myself in saying that we did not know where the three boys would now be. We would not be expected to know, beyond a general feeling or conviction that they would by now be concealed in the loft of the barn or stable — this from previous experience, though experience had never before included or comprised arson. Nor do I feel that I further violate the formal rules of order, unity and emphasis by saying that we would never for one moment have conceived them to be where later evidence indicated that they now were.

But more on this subject anon: we were not thinking of the boys now; as Mr. Faulkner himself might have observed, someone should have been thinking about them ten or fifteen minutes ago; that now it was too late. No, our concern was to reach the pasture, though not with any hope of saving the hay which had been Mr. Faulkner’s pride and even hope — a fine, though small, plantation of this grain or forage fenced lightly away from the pasture proper and the certain inroads of the three stocks whose pleasance the pasture was, which had been intended as an alternative or balancing factor in the winter’s victualing of the three beasts.

We had no hope of saving this, since the month was September following a dry summer, and we knew that this as well as the remainder of the pasture would burn with almost the instantaneous celerity of gunpowder or celluloid. That is, I had no hope of it and doubtless Oliver had no hope of it. I do not know what Mr. Faulkner’s emotion was, since it appears (or so I have read and heard) a fundamental human trait to decline to recognize misfortune with regard to some object which man either desires or already possesses and holds dear, until it has run him down and then over like a Juggernaut itself.

I do not know if this emotion would function in the presence of a field of hay, since I have neither owned nor desired to own one. No, it was not the hay which we were concerned about. It was the three animals, the two horses and the cow, in particular the cow, who, less gifted or equipped for speed than the horses, might be overtaken by the flames and perhaps asphyxiated, or at least so badly scorched as to be rendered temporarily unfit for her natural function; and that the two horses might bolt in terror, and to their detriment, into the further fence of barbed wire or might even turn and rush back into the actual flames, as is one of the more intelligent characteristics of this so-called servant and friend of man.

So, led by Mr. Faulkner and not even waiting to go around to the arched passage, we burst through the hedge itself and, led by Mr. Faulkner who moved at a really astonishing pace for a man of what might be called almost violently sedentary habit by nature, we ran across the yard and through Mrs. Faulkner’s flower beds and then through her rose garden, although I will say that both Oliver and myself made some effort to avoid the plants; and on across the adjacent vegetable garden, where even Mr. Faulkner could accomplish no harm since at this season of the year it was innocent of edible matter; and on to the panel pasture fence over which Mr. Faulkner hurled himself with that same agility and speed and palpable disregard of limb which was actually amazing — not only because of his natural lethargic humor, which I have already indicated, but because of that shape and figure which ordinarily accompanies it (or at least does so in Mr. Faulkner’s case) — and were enveloped immediately in smoke.

But it was at once evident by its odor that this came, not from the hay which must have stood intact even if not green and then vanished in holocaust doubtless during the few seconds while Oliver was crying his news, but, from the cedar grove at the pasture’s foot. Nevertheless, odor or not, its pall covered the entire visible scene, although ahead of us we could see the creeping line of conflagration beyond which the three unfortunate beasts now huddled or rushed in terror of their lives.

Or so we thought until, still led by Mr. Faulkner and hastening now across a stygian and desolate floor which almost at once became quite unpleasant to the soles of the feet and promised to become more so, something monstrous and wild of shape rushed out of the smoke. It was the larger horse, Stonewall — a congenitally vicious brute which no one durst approach save Mr. Faulkner and Oliver, and not even Oliver durst mount (though why either Oliver or Mr. Faulkner should want to is forever beyond me) which rushed down upon us with the evident intent of taking advantage of this opportunity to destroy its owner and attendant both, with myself included for lagniappe or perhaps for pure hatred of the entire human race.

It evidently altered its mind, however, swerving and vanishing again into smoke. Mr. Faulkner and Oliver had paused and given it but a glance. “I reckin dey all right,” Oliver said. “But where you reckin Beulah at?”

“On the other side of that —— fire, backing up in front of it and bellowing,” replied Mr. Faulkner. He was correct, because almost at once we began to hear the poor creature’s lugubrious lamenting. I have often remarked now how both Mr. Faulkner and Oliver apparently possess some curious rapport with horned and hooved beasts and even dogs, which I cheerfully admit that I do not possess myself and do not even understand. That is, I cannot understand it in Mr. Faulkner.

With Oliver, of course, cattle of all kinds might be said to be his avocation, and his dallying (that is the exact word; I have watched him more than once, motionless and apparently pensive and really almost pilgrim-like, with the handle of the mower or hoe or rake for support) with lawn mower and gardening tools his sideline or hobby. But Mr. Faulkner, a member in good standing of the ancient and gentle profession of letters! But then neither can I understand why he should wish to ride a horse, and the notion has occurred to me that Mr. Faulkner acquired his rapport gradually and perhaps over a long period of time from contact of his posterior with the animal he bestrode.

We hastened on toward the sound of the doomed creature’s bellowing. I thought that it came from the flames perhaps and was the final plaint of her agony — a dumb brute’s indictment of heaven itself — but Oliver said not, that it came from beyond the fire. Now there occurred in it a most peculiar alteration. It was not an increase in terror, which scarcely could have been possible. I can describe it best by saying that she now sounded as if she had descended abruptly into the earth.

This we found to be true. I believe however that this time order requires, and the element of suspense and surprise which the Greeks themselves have authorized will permit, that the story progress in the sequence of events as they occurred to the narrator, even though the accomplishment of the actual event recalled to the narrator the fact or circumstance with which he was already familiar and of which the reader should have been previously made acquainted. So I shall proceed.

Imagine us, then, hastening (even if the abysmal terror in the voice of the hapless beast had