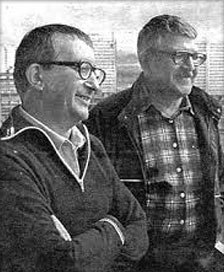

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

Arkady Natanovich, August 28, 1925, Batumi – October 12, 1991, Moscow and Boris Natanovich April 15, 1933, Leningrad – November 19, 2012, St. Petersburg Strugatsky – Russian Soviet writers, screenwriters, one of the few Soviet authors of science and social fiction who found themselves in demand after the collapse of the USSR.

In the second half of the 1950s, military translator A. N. Strugatsky, with the help of journalist L. Petrov and writer and intelligence officer R. Kim, published the documentary story “Bikini Ashes” (magazine versions 1956 and 1957, book edition 1958) and got a job position of editor at Goslitizdat. B. N. Strugatsky, who worked at the Pulkovo Observatory, also had literary ambitions; According to legend, the brothers decided to write together as a bet. In 1957-1959, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky wrote the story “The Country of Crimson Clouds” and several short stories that immediately attracted the attention of critics. In 1964, the Strugatskys were admitted to the USSR Writers’ Union. After many years of experimentation, a working method was developed that included not only a joint discussion of ideas, but also the verbal pronunciation of each phrase. Work on the text proceeded according to a detailed plan, which was developed in advance and discussed many times.

Starting with works in the synthetic genre of adventure and science-technical fiction, the Strugatskys quickly moved on to social prognostication and modeling in the form of “realistic fiction”, the ideological content of which is wrapped in a sharp plot. Most of their books are devoted to establishing contact with another mind, considering the issue of the admissibility and justification of intervention or non-interference in the natural evolution of civilizations of any type, and studying different forms of utopia. Much space in their work was devoted to the problem of ideologization and de-ideologization of society and the role of culture in the state. In the first half of the 1960s, the Strugatskys created a single fantastic metaworld, conventionally called the “World of Noon,” in which the action of almost a dozen stories takes place. The image of communism they built evolved towards permanent geopolitical and “geocosmic” expansion and associated mechanisms of social control. Consideration of various forms of utopia led the Strugatskys (starting with “Distant Rainbow”) to the conviction of the inevitability of the split of humanity into strata of unequal numbers, not all of whose representatives are worthy and suitable for entering a bright future. The co-authors were also concerned about the prospect of creating a biological civilization that would radically reconstruct human nature and oppose technical culture. Beginning in the 1980s, B. N. Strugatsky began to rethink his creative path with his brother-co-author in line with liberalism and dissidence.

Having achieved great fame in the 1960s, the Strugatskys fell into a period of persecution against philosophical fiction in the USSR by the Department of Agitation and Propaganda of the CPSU Central Committee and the leadership of the Komsomol. In the 1970s – the first half of the 1980s, the number of publications and reprints decreased, a number of voluminous texts acquired a semi-forbidden status and were circulated in samizdat (“Ugly Swans”). Based on the then unpublished story “Roadside Picnic,” the Strugatskys wrote the script for the film “Stalker” (1979) for A. Tarkovsky. In the 1980s, the Strugatskys became one of the most published Soviet writers, a symbol of independence of thought, and were awarded the State Prize of the RSFSR named after M. Gorky (1986). In 1991-1994, the Text publishing house published the first collected works of the Strugatskys. In the 1990s, many publications were published, including the series “The Worlds of the Strugatsky Brothers.” A team of Strugatsky researchers (the so-called “Ludens Group”) in 2001-2003 published an 11-volume collection of works based on archival texts, and in 2015-2022 – a complete collection of Strugatsky works in 33 volumes.

The Strugatskys’ work had a noticeable influence on the spread of dissent among the Soviet intelligentsia in the 1970s and 1980s. The works of the Strugatskys were actively studied by literary scholars (A. F. Britikov (1970), A. A. Urban (1972), Darko Suvin (1974), M. F. Amusin (1988, 1996), S. Potts (1991), I. Howell (1994), I. Kukulin, I. Kaspe, etc.), social philosophers (V. Serbinenko, B. Mezhuev), political scientists (Yu. Chernyakhovskaya), who sometimes offered polar opposite interpretations of texts and ideological constructs created by writers. Summary literary biographies of the Strugatskys, based on archival materials, interpreted based on different ideological and political premises, are presented by science fiction writer Ant Skalandis (2008) and co-authored by historian D. Volodikhin and writer G. Prashkevich (2012).

Origins of creativity

Cultural and socio-political environment of formation of the Strugatsky brothers

The fundamental feature of the Strugatsky brothers’ work is its collective nature. Between 1941-1956, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky lived far from each other, they were not united by either professional activities or everyday life; Communication mostly took place in written form. The circumstances of the formation of the personalities of both brothers and their socio-political and aesthetic views were completely different. In particular, despite the small difference in age (about eight years), Arkady and Boris belonged to different generations in their worldview: in 1941, the eldest of the brothers was 16 years old, and his childhood years fell in an era “for which it was then customary to speak” “Thank you” Comrade Stalin. Without any irony and without any “buts” in this case: a peaceful, calm life in a good family, among good friends, in a wonderful city, in a beloved country, which both adults and children were sincerely proud of.” The time of formation of Boris Strugatsky’s personality occurred during the war, blockade and evacuation, which predetermined negative memories of his childhood and youth and a skeptical attitude towards the country and the political system.

The socio-political preferences of the Strugatsky brothers were formed in completely different environments. Arkady Strugatsky, having graduated from the Military Institute of Foreign Languages, received the specialty of an officer-translator from Japanese and English and in 1946-1954 had experience working with secret documents and interrogating prisoners of war and war criminals. After returning to Leningrad, Boris Strugatsky lived the ordinary life of an intelligent schoolboy and student, graduating from Leningrad University (Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics). Their life-meaning orientations came closer under the influence of constant correspondence and rare meetings during Arkady’s vacations spent in Leningrad. After the demobilization of the eldest brother in 1956, he settled in Moscow, meetings with his brother and correspondence became much more intense, but the main circle of contacts and friends remained different until the end of his life, although he belonged to the Soviet scientific, technical and artistic elite (including Naum Korzhavin and Vladimir Vysotsky). The path of both brothers to literature fell on the period of the “thaw” and the scientific and technical romanticism it generated, which was very fruitful for social design.

The Strugatskys’ reading circle, which provided them with pretexts and samples for developing their own literary style, was unique. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky were interested in philosophy, studying the works of the classics of Marxism-Leninism, not only for official or academic duties. Both appreciated Russian classical literature, indicating that they learned to write from N.V. Gogol, L.N. and A.N. Tolstoy. Arkady Strugatsky, fluent in Japanese and English, professionally followed literary innovations for many years; apparently he read Orwell early on. Many Japanese authors were available to him in the original, including Akutagawa, Kikuchi Kan, and Arishima Takeo. At the same time, A. Strugatsky was indifferent to Japanese poetry; all epigraphs and quotes from Japanese authors were selected by Boris Natanovich. Since childhood, both brothers loved adventure literature and science fiction, preferring foreign authors. Most of the books by Kipling, Dumas, Wells, Jacolliot and other writers were impossible to obtain on sale or in public libraries, and they came from the book collections of parents or friends.

The path to literature. Author’s tandem

According to the memoirs of Arkady Strugatsky, his father Nathan Zalmanovich attracted him to literature, including science fiction, by telling him in childhood “an endless novel created by himself based on the plots of the books of Mine Reed, Jules Verne, Fenimore Cooper.” The eldest of the Strugatsky brothers made attempts to write fantastic prose back in the late 1930s (according to B. N. Strugatsky, it was the story “The Find of Major Kovalev,” lost during the Leningrad blockade). Stories of this kind were composed orally and spoken out together with a friend and neighbor in the stairwell, Igor Ashmarin, sometimes the younger brother Boris was allowed to participate in the “literary feast.” A letter dated May 20, 1943, when Arkady was studying at an artillery school, was preserved and mentioned the story they wrote together with Boris about the adventures of his mother and younger brother in besieged Leningrad (“Write to me in more detail how you are working on the story and according to what plan”). Arkady was then seventeen years old, Boris was ten. The texts preserved in the archive date back to a later period, especially to A. Strugatsky’s service in Kamchatka, which left him with free time.

The literary “godfather” of the Strugatsky brothers turned out to be Roman Kim, a counterintelligence officer who worked in the Japanese direction and was a well-known writer of the adventure genre in the Soviet Union. Biographers disagree about when their acquaintance took place. The brothers’ correspondence in 1952 mentions Kim’s story “The Notebook Found in Sunchon,” which Arkady persistently recommended for Boris to read. Direct acquaintance could have taken place in 1954 or 1958 (in the latter case there is documentary evidence). In 1954, Arkady Strugatsky wrote a documentary story “Bikini Ashes” (about the fate of the crew of the fishing schooner “Fukuryu-maru”), which his colleague, Sovinformburo employee Lev Petrov, undertook to “punch through”. Petrov managed to arrange publication in the Far East magazine, and in April 1956 R. N. Kim became the editor of the story. According to the assumption of local historian Viktor Petrovich Buri, Arkady Strugatsky could not help but take part in editing the story, thus, his acquaintance with Kim dates back to April 1956. The decision to publish was made in August 1956, the royalties were divided in half; both Strugatsky and Petrov had already settled in Moscow by that time. Roman Kim oversaw the science fiction direction at the Writers’ Union and in 1963 actively helped the Strugatskys, emphasizing that “abroads are waging a broad anti-Soviet and anti-communist offensive in science fiction.” Accordingly, the Strugatskys considered him one of the most important figures who ensured the rise of Soviet science fiction.

In 1958, when the Strugatskys were awaiting the publication of their debut story “The Country of Crimson Clouds” in the editorial office of “Detgiz”, R. Kim organized the release of a specialized almanac of fantasy and adventure and ordered the story “From the Outside” from Arkady Strugatsky. At the same time, I met Ivan Efremov. In December 1960, R. Kim, I. Efremov and critic K. Andreev gave the Strugatskys a recommendation to join the Union of Soviet Writers. The admission procedure was delayed for a number of reasons (despite the fact that the subsection of adventure and science fiction twice recommended speeding up the process), and only on February 25, 1964, at the selection committee of the Writers’ Union, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky were elected by nine votes with five abstentions. Secondary recommendations were provided by I. Efremov, K. Andreev and A. Gromova.

After 1966-1968, the attitude towards fantastic literature (especially the philosophical fiction developed by the Strugatskys) changed at the level of the Department of Agitation and Propaganda of the CPSU Central Committee and the Komsomol Central Committee. This was expressed in the issuance of closed decrees regulating publishing policy in the field of science fiction, and critical campaigns launched in the press against specific writers and works. Serious conflicts between the co-authors and the party authorities occurred in 1968 and 1972 in connection with the publication of the story “The Tale of Troika” in the anthology “Angara” and the publication of the story “Ugly Swans” in the emigrant publication “Grani”. After 1968, three works by the Strugatskys (“The Tale of Troika”, “Snail on the Slope”, “Ugly Swans”) gradually became uncensored literature distributed in samizdat.

The Strugatskys’ attempts to distance themselves from publications in emigrant publications in Europe were unsuccessful, even despite a refutation in Literaturnaya Gazeta in 1972. Each of these publications further alienated the authors from the official press. Significant for the Strugatskys in their relations with the authorities and at the same time in the publishing policy of the USSR in the field of science fiction was the history of the publication of the story “Roadside Picnic,” which lasted ten years. In 1970, the authors submitted an application to the editors of the Young Guard for the collection “Unassigned Meetings” (“From the Outside,” “Baby,” “Roadside Picnic”), which was published after repeated reminders and even lawsuits in 1980. In 1974, the KGB showed interest in B.

Strugatsky in connection with the case of his friend Mikhail Kheifetz, who was arrested for distributing his own article “Joseph Brodsky and Our Generation” (preface to the so-called “Maramzin collection” of Brodsky’s works). Boris Strugatsky and his wife Adelaide (née Karpelyuk) were witnesses. Emotional experiences were reflected in the tone and plot idea of the story “A Billion Years Before the End of the World.” Although in the 1960s and 1970s in Soviet non-realistic literature the Strugatskys (like I.A. Efremov) represented the liberal reformist trend, they could not be classified as dissidents and anti-Sovietists; Until the very last years, they demonstrated loyalty to the authorities.

In the creative tandem, Arkady Natanovich and Boris Natanovich changed roles over time. According to the testimony of the youngest of the brothers, in the decade 1955-1965, the eldest – Arkady – “was… assertive, incredibly able-bodied and hardworking, and was not afraid of any work in the world. Probably, after the army, this civilian world seemed to him a container of unlimited freedoms and incredible opportunities.” It is noted that twenty years later, dominance (in terms of plot and publishing initiatives) clearly passed to Boris Strugatsky. By the beginning of 1991, a breakdown came when, in the words of A. Skalandis, “it became completely impossible to combine what they invented and wrote now.” The last meeting of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky took place in Moscow on January 16-19, 1991 and ended in a serious quarrel, possibly related to the illness of the eldest brother. However, in the work diary kept by both co-authors, the entry “The writer “the Strugatsky brothers” is no more” was made by B. N. Strugatsky on October 13, the day after his brother’s death.

Literary technique. Co-authored work

The co-creation of two brothers who lived and worked in different cities distinguished the Strugatskys from the point of view of literary technique. In interviews, the writers laughed it off, which is why a legend arose that they met to work at Bologoye station, halfway between Leningrad and Moscow. In fact, the development of co-creation methods dragged on for more than a decade and finally took shape by 1960. For a long time, the initiator of the projects of the creative tandem was Arkady Natanovich, who, while serving in the army (in Siberia, Kamchatka and the Far East), tried himself in writing stories and novellas, while Boris Natanovich acted as the first reader, reviewer and consultant on “ technical issues.” In the second half of the 1950s, when Arkady Strugatsky was demobilized and worked as an editor in various publishing houses in Moscow, the brothers did not abandon the idea of joint creativity. However, the technique used during the writing of “The Land of Crimson Clouds” is defined by A. V. Snigirev as “strange”: the co-authors wrote independently, sending each other finished chapters, fragments and parts. This technique was perceived by the Strugatskys themselves as “defective” back in their correspondence in 1956. In the future, Boris Natanovich often acted as a “generator of ideas” that Arkady embodied in the text, but the eldest of the brothers insisted that they needed to write together: “The ABS company must act as a united front.”

In 1958, the co-authors tried and rejected the concept of “stepped editing,” when Arkady sent Boris chapters as they were ready and received them back after editing. At the same time, the brothers tried to experiment in different genres and forms: the older one wrote novels, the younger one wrote short stories. Sometimes they switched roles. The story “Sand Fever” dates back to 1955, written impromptu, like a storm, without any preliminary plan, but in the end it turned out to be a solid thing. In addition to working with the text, a lot of trouble was caused by communicating with magazine editors and publishing house management, conducting ongoing correspondence and business meetings, which caused conflicts over the distribution of responsibilities back in the 1960s, when the brothers were actively publishing and became sought-after writers. The method of working in collaboration finally took shape either by the time of the completion of “The Country of Crimson Clouds”, or when writing the story “The Path to Amalthea” in 1959. In his retrospective “Comments on what has been accomplished,” B. N.

Strugatsky argued that the co-authors, having tried all imaginable schemes and options for working together, through trial and error, created the final technique, which they adhered to until the very end of their creative tandem.

The specificity of the work of ABS, when any more or less serious text must be created by two people, at the same time, word by word, paragraph by paragraph, page by page; when any phrase in a draft has as its predecessors two or three or four phrases proposed as options, once spoken out loud, but not written down anywhere; when the final text is a fusion of two – sometimes very different – ideas about it, and not even an fusion, but a kind of chemical compound at the molecular level – this specificity gives rise, among other things, to two consequences that are purely quantitative in nature.

Firstly, the amount of paper in archives is reduced to a minimum. Each novel exists in the archive in the form of only one, maximum two drafts, each of which is actually written down on paper, edited and compressed text of two or three or four ORAL drafts, spoken at one time by the authors and polished more or less in the process fierce debate.

Relatively short working meetings (first at the co-authors’ homes, after they joined the Writers’ Union – in creative houses) were preceded by a long preparation of the material. Work began only after the preliminary development of a plan for the work, sometimes down to the smallest detail (including the arrangement of mise-en-scène or even key phrases). The writing process, in the words of B. N. Strugatsky, was “adding meat to the skeleton”: the text was the result of continuous dialogue, discussion in the literal sense of every word and phrase. Further work with the text, associated with editing and censorship, was also intensive, although B. Strugatsky most often assessed it negatively. However, according to A.V. Snigirev, the published draft and preparatory materials allow us to conclude that the proposals of editors and censors made the texts much higher quality both from an artistic and ideological point of view, and contributed to more accurate work on each word and the entire content of the text. According to A.V. Snigirev, the Strugatskys’ texts, which are of an “internal” nature or not intended for publication, clearly demonstrate a certain “weakness” in comparison with the published ones.